Exercise Addiction: What is it? (and how I’m over coming it)

Guest blog written by Nick Roberts | @newfie_bullet84 | 12 minute read

“I’m not doing enough.”

Though there are many possible triggers for Exercise Addiction (body dysmorphia, pressure to perform, sense of identity, etc), they all stem from a deeper sense of one common thought pattern, which is some form of "I'm not good enough".

I want to share with you my own personal battle with it, how I came to realize that I am prone to EA, and ways for anyone to accept and manage that they may in fact have some form of the addiction.

What is Exercise Addiction? Isn’t more always better?

EA occurs when they cross the line where continuing to exercise becomes detrimental to them. It is a type of compulsive disorder that results in anxiety when either the person feels they are not exercising enough, or as a means to escape life, despite leading to ailments/injuries/illnesses.

The British Journal of Sports Medicine has identified two types of Exercise Addiction, a Primary and Secondary. Primary EA happens when the exercise is the main purpose of the practice, while Secondary EA is when it is used as a means to control weight or an eating disorder. With either one, excessive training leads directly to chronic health problems such as adrenal burnout, hormonal dysfunction, chronic inflammation, etc.

There are some sports that inherently promote levels of exercise that do not constitute optimal health. These can include Crossfit, Triathlon, Ultramarathon, and many sports practiced at the highest levels such as Weightlifting, martial arts, etc. Training for Special Operations also often falls into this category given the nature of how brutal the selections and courses are regarding various elements of physical fitness and stamina. You will NEVER be fit enough essentially.

Recently the term "Hybrid Athlete" has been widely used to categorize how athletes choose not to specialize in a particular activity, but concurrently train for (and often compete in) multiple events. The total weekly training volume when combining programs involving things like Powerlifting and Marathon training can have athletes training up to 12-14 times per week in total, often while holding full time jobs and social lives/families.

The line between commitment and compulsion

To achieve anything in this life, you've got to commit. I mean REALLY fucking commit. Sacrifices have to be made (through prioritization mainly), compromises, and living a way that is "different" than most. There's no getting around this if you want to be great, especially in physical endeavours.

How can you determine if you're crossing the line between Commitment, and Compulsion? It may not always be clear, and certainly means different things to everyone. However, ask yourself these types of questions:

Do you experience significant anxiety if you are unable to train, or worse, if you aren't ALWAYS training/preparing to train?

Are you developing other interests, skills and knowledge outside of your chosen physical activities?

Does your entire personal identity surround with not just results, but the ACT of training?

Are you training to the point of extreme exhaustion, and abusing every type of pre-workout/nootropic/PED/etc. available in order to simply get yourself moving?

When was the last time you took a proper de-load, or even BREAK, from training altogether?

The list can go on, but you probably get the idea. Committed people push themselves hard, make the sacrifices, and prioritize. Compulsive exercisers can never do "enough", and are addicted to the feeling of training (which has some similarities to a drug addiction, as there are psychoactive chemicals that circulate during exercise), and will often do way more than necessary, even to their detriment.

If you're like me, it took a long time to fully understand myself and what was happening to me both physically and mentally. It wasn't just a few months of "Man, my results are getting worse instead of better this past 1-2 cycles of training". It occurred gradually over DECADES, culminating in my pursuit of Special Operations as a challenge I set for myself.

Little by little, I did more and more, got up earlier and earlier, ate less and less. The worse my results, the more I pushed. When I wasn't happy with my physique/body composition (despite actually being quite lean), I resorted to longer bouts of Fasting, more ketogenic nutritional strategies, and this bravado of "I'm fine, I don't even need to eat to perform".

Though I recognized that I may have EA long before the final straw, there was a certain attachment I had developed to training as much as I did, and the nutritional habits that came over time. The anxiety around doing LESS was crushing me, as I suddenly had more time on my hands, wasn't always in preparation or training mode, and hadn't developed enough relationships or interests outside of training to fill the void.

Something finally clicked though, and life (and my results!) have been improving ever since.

My back story and the downward spiral

"It's not how hard you can hit, it's how hard you can get hit, and keep moving forward. How much you can take, and keep moving forward." -Rocky Balboa

At my peak strength in January 2018, I put up these numbers on a training day:

Squat: 305kg/672lb

Bench: 190kg/418lb

Deadlift: 325kg/716lb (cheater Sumo)

Body weight: 103kg/227lb

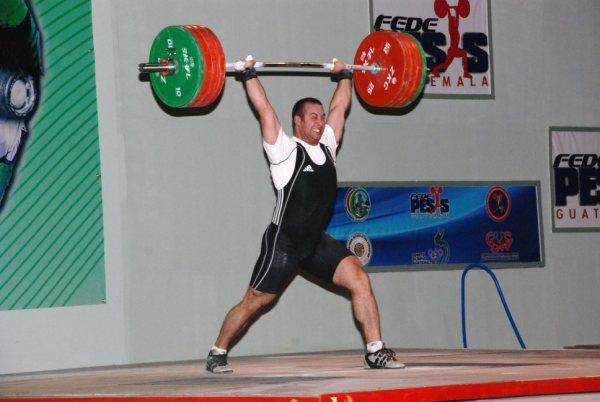

Though my initial 12-13 years of training focused on Olympic Weightlifting, where I had National Records and titles, I found myself more naturally drawn to Powerlifting once my Weightlifting career was over. It fit my personality well, along with my genetics and understanding of how to build strength.

A few days after that 820kg training total, I strained my right adductor. Badly enough that I could not compete at the 2018 Canadian Championships about 6 weeks after. During this time, frustrations with sustaining random injuries at the wrong times led to me wanting to make big changes to my fitness and health goals. While it was a lot of fun being that strong and eating to be over 225lb (which was uncomfortable for me), I wondered what else I could achieve with this body. I had been looking into Intermittent Fasting protocols and was intrigued, and also wanted to regain my childhood fitness from Hockey and Soccer where I could run very well. Calisthenics suddenly appealed to me, as it combined strength with skill, rewarding a lighter body with more abilities.

In 6-8 months, I had lost 35lb of bodyweight, mostly from fat. Fasting was something I very much enjoyed and to this day believe in, with several caveats. I do not use it for fat loss as much as cognitive functioning, metabolic flexibility, and ease of planning meals. However as the years went on, I fasted too long, too often, with far too much activity to make it sustainable. I was lifting EVERYDAY, running/conditioning EVERYDAY, and almost never doing a proper deload or taking any breaks. The resultant compensations in my body were massive losses in strength, muscle mass, and crushing my hormones. Blood work from January-August 2023 showed near hypogonadal Testosterone levels, a genetic disorder called Hemochromatosis, extremely high inflammatory markers, among other things.

In essence, I had trained myself into poor health and accumulated more injuries despite losing a ton of strength.

The final "wakeup call" was when, during a Bench that wasn't even remotely heavy compared to my strength of the past, caused a partial pec tear. The surgeon and I had a heart to heart conversation, informing me that I have osteoarthritis in my shoulders, hips, and knees, and if I don't change how I'm doing things, this may continue to happen.

Getting back up and the way forward

A change of scenery back to Montreal (a place that feels like home), and a plan to alter my career path (out of the military), helped pave the way to overcoming Exercise Addiction. The main changes that have occurred (and are still ongoing, as with any addiction, you will always deal with it):

I still train everyday, but with less volume. Workouts typically only last 60-75min, including proper warm-ups.

I deload more often, mostly instinctively, with a "live to train another day" attitude. Working through pain is no longer an option, or forcing loads that don't need to be lifted on that day.

I don't run or do conditioning everyday, as strength/hypertrophy are my current priority. I walk everyday, and throw in some running while out IF I FEEL LIKE IT. I still enjoy running, but realize I can't chase too many rabbits, and will sacrifice being better at running in order to pursue what makes me feel like myself, which is to be strong.

I eat more! My diet revolves mostly around a Carnivore type approach, with small amounts of carbs depending on what my goals and expenditures are looking like. Oddly enough, I'm leaner than when I was training more and eating less.

I spend more time with my partner. I read more. I am learning to not feel guilty about not exercising like a professional athlete (though this one is tougher to overcome than you'd think, since for over 20 years I did train like one).

To say that I've cured the addiction would be dishonest. I've essentially made concessions to allow for me to gradually get away from the self destructive habits and thought processes, rather than force it. I still desire to be active multiple times per day. I still have trouble accepting the amount of food I need to intake in order to achieve my goals. I still look back at my old numbers sometimes instead of looking forward and treating the current training as a sort of "post trauma PR's" or something.

My strength is on the rise for the first time in over 5 years, with improved health markers, quality of life, and reduced feelings of anxiety and depression.

The turnaround has been faster than expected, likely due to just how much I was destroying myself day in and day out. I'm hopeful that aspects of previous performances can be renewed, but I don't need it to be happy and healthy.

Feeling good and being healthy is finally "enough".

Winning the war

It is perhaps a little odd that in a world where getting the majority of the population to do ANY regular, purposeful, engaging physical activity is a huge problem, that some of us take it so far in the other direction that we end up with health problems of our own. You'd much rather see a world of people with EA than the amount of obesity and diseases that are the current norm.

Let's make no mistake though: too much exercise and too little nutrition can make you ill (and possibly even kill you).

Exercise Addiction should be treated much like other addictions, perhaps without as much formality as say AA meetings, but should be talked about openly. Discussing our anxieties and tendencies with others (even if they don't fully understand), helps to normalize the issue instead of continuing down the lonely spiral of inadequacy.

If you can look yourself in the mirror and be honest about your relationship with exercise, nutrition, your body, and your identity relative to your results/feelings/health/etc, that's at least the first step in overcoming the addiction.

Next is to find help. Your coach, other athletes, mental health professionals, etc. Support is critical, and while YOU need to do the work, the right people in your corner is essential.

Be patient with yourself, and do not expect perfection. Notice trends of old habits and thought processes. Keep a journal if you have to.

When in doubt, rest and recover. Get a massage or go to a recovery spa. Replace planned training with a hike, walk somewhere new, a bike ride, skiing, etc.

Ensure nutrition is optimal for performance and health first, and body composition second. Don't allow images of perfect bodies influence what you need to consume for your body. They are so often Photoshopped, enhanced, and temporary anyways. And they often don't feel great at that time either.

Set boundaries on the length of time you can train. Be focused, eliminate distractions, do enough quality sets to create stimulus for adaptations (minimum effective dose), and get out of there.

Listen to your body. One workout never made anyone strong or fit, but one rep/lift can set you back days/months/years/permanently. Remember to live to train another day and avoid the ego lifting. The program you have (even from an experienced coach) is just a guide.

Warm-up better. Develop a go-to plan for how to warm-up for various types of training sessions, and don't deviate. If that means you get less done in the gym, so be it. Better than tweaks and poor performance.

Cut accessories. If something has to go, it's the fluff at the end of the session. Put your time and effort into the biggest bang for your buck movements, and call it a day. Those few sets of tricep pushdowns aren't really going to matter much if you trained your presses hard and smart.

Remember, it's just a workout. There's more to life than your training. Give your best effort, but don't live and die by your performance or physique.

Strong mind, strong body. Resilience.

Coach Nick